INDIGENOUS ARTS

Keeping the rich traditions of American Indian culture alive is a key objective of the Indigenous Arts program at Holbrook Indian School (HIS). Pottery making, weaving, beading, Navajo government, American Indian history, and Diné (Navajo) language are integral to connecting our students to their rich cultural heritage, while graphic arts and design classes help develop students’ digital arts talents.

Because the majority of students at HIS are Navajo or Diné (meaning “The People”), HIS works to facilitate healing in identity by providing classes in Navajo history, government, and language, as well as Indigenous arts.

Navajo language and Navajo government classes are both taught by Sam Hubbard, who is Diné (this is how members of the Navajo Nation refer to themselves). “My favorite aspect of teaching is probably when students learn new things and they tell you about it,” Sam said. “Many times, students have learned something new that they probably would have never learned if they were at another school. Our school is unique.”

Sam adds that though many students come from the reservations, they know more about pop culture than they do about their history and traditions. “We want them to not feel ashamed of their Native heritage.”

DINÉ LANGUAGE

In the early American Indian boarding schools, children were often punished for speaking in their Native languages. Yet ironically, American Indian languages played an important role in the positive outcomes of World Wars I and II, where American Indians fluent in their traditional languages were used to send secret messages in battle. The most famous among these are the Navajo Code Talkers. Throughout the years, many students have attended HIS whose fathers, uncles, grandfathers, and great uncles were Code Talkers. Today, most students do not speak in their Native language. Yet many of their grandparents only speak Diné. By teaching students Diné, HIS hopes to help reconnect Navajo youth with their elders.

NAVAJO HISTORY

Many people are familiar with the Trail of Tears, but few have heard about the Long Walk. During the 1860s, Kit Carson began his campaign against the Navajo by using a “scorched earth policy,” in which he burned their crops and destroyed food stores in an effort to ruin their ability to sustain themselves. This destructive war resulted in the removal of the Navajo from their homeland of the Four Corners area (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona) to Southeastern New Mexico. Carson forced more than 8,500 men, women, and children to walk across New Mexico for imprisonment at the Bosque Redondo Reservation, over 400 miles from their homes. Along the way, 200 Diné people died from exposure and starvation. Upon arrival, the Diné were given poor food that led to illness and famine. Deprivation, disease, and death plagued the Diné. In total, one out of four people died. Eventually, the military admitted the effort a failure and allowed the Diné to return home. As part of their history class, students retrace the steps of the Long Walk to help them understand the experiences of their ancestors that affect their lives today.

NAVAJO NATION GOVERNMENT

Today, the Navajo Nation extends into the states of Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico and covers 27,000 square miles. Since a tribal government was first established in 1923, the Navajo Nation has evolved into the largest and most sophisticated form of Native American government in the United States. Every year, HIS students visit the Navajo Nation capital in Window Rock as part of their Navajo government class, learning first hand how its three-branch system of government operates.

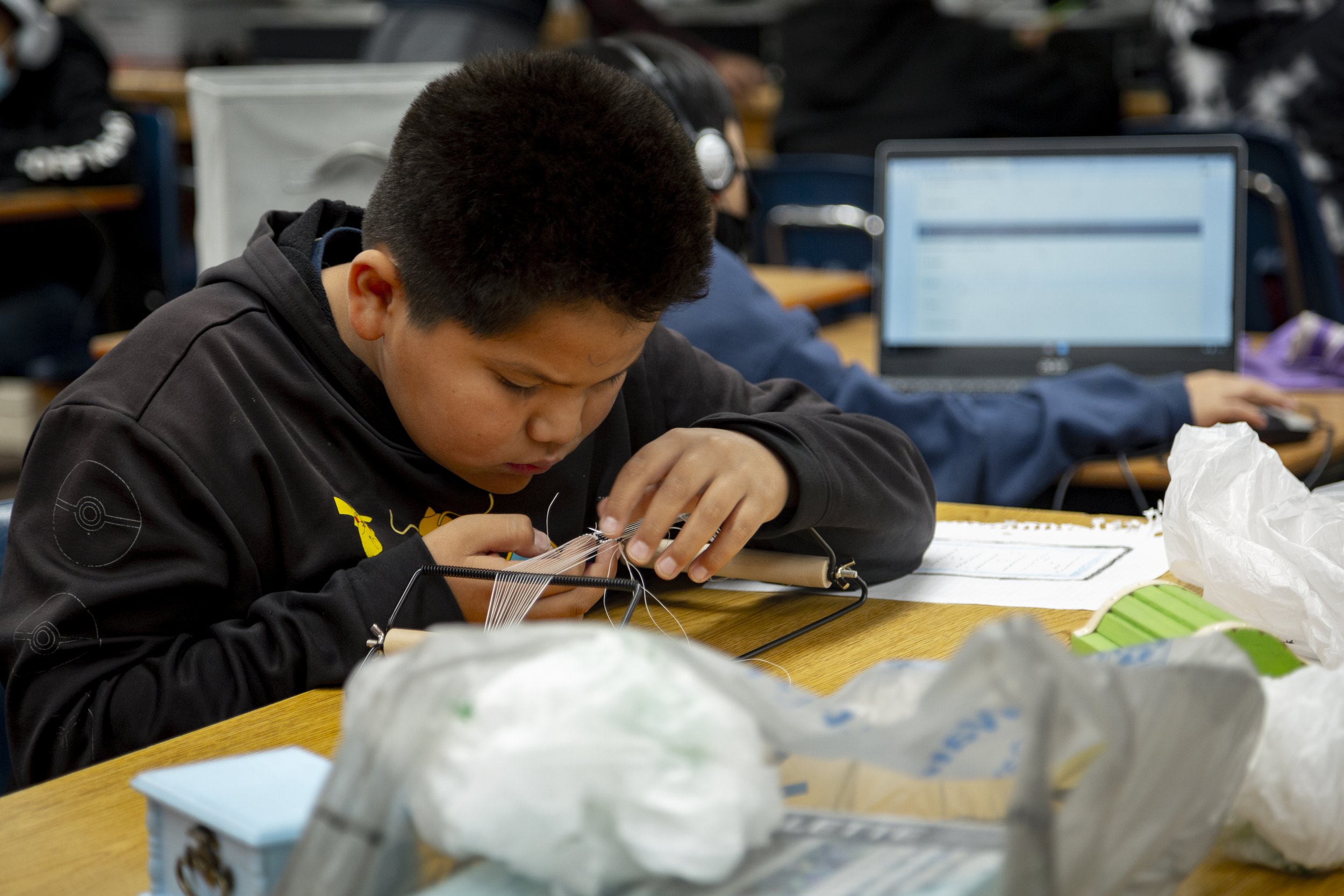

INDIGENOUS ARTS

Pottery making, weaving, and beading are fast becoming lost skills. The Indigenous Arts program at HIS focuses on traditional practices while inspiring students to tap into their creativity and to connect with their culture.

Art has a special way of reaching students, said Zak Adams, founder of the Indigenous Arts program. “They can use it to express themselves when words can’t. What I have seen of our students is that they are starving for their own culture,” said Zak.

Art provides many benefits for mental health and emotional wellbeing, which include a sense of accomplishment, an increase in drive, and improved concentration. Studies suggest that art can be valuable in treating depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Support Indigenous Arts

When you give to the Indigenous Arts program, you are helping students to connect with their rich cultural history and keep traditions alive. Programs like this are only possible through the support of people like you.

To find out more about the needs of our Indigenous Arts program, contact us.

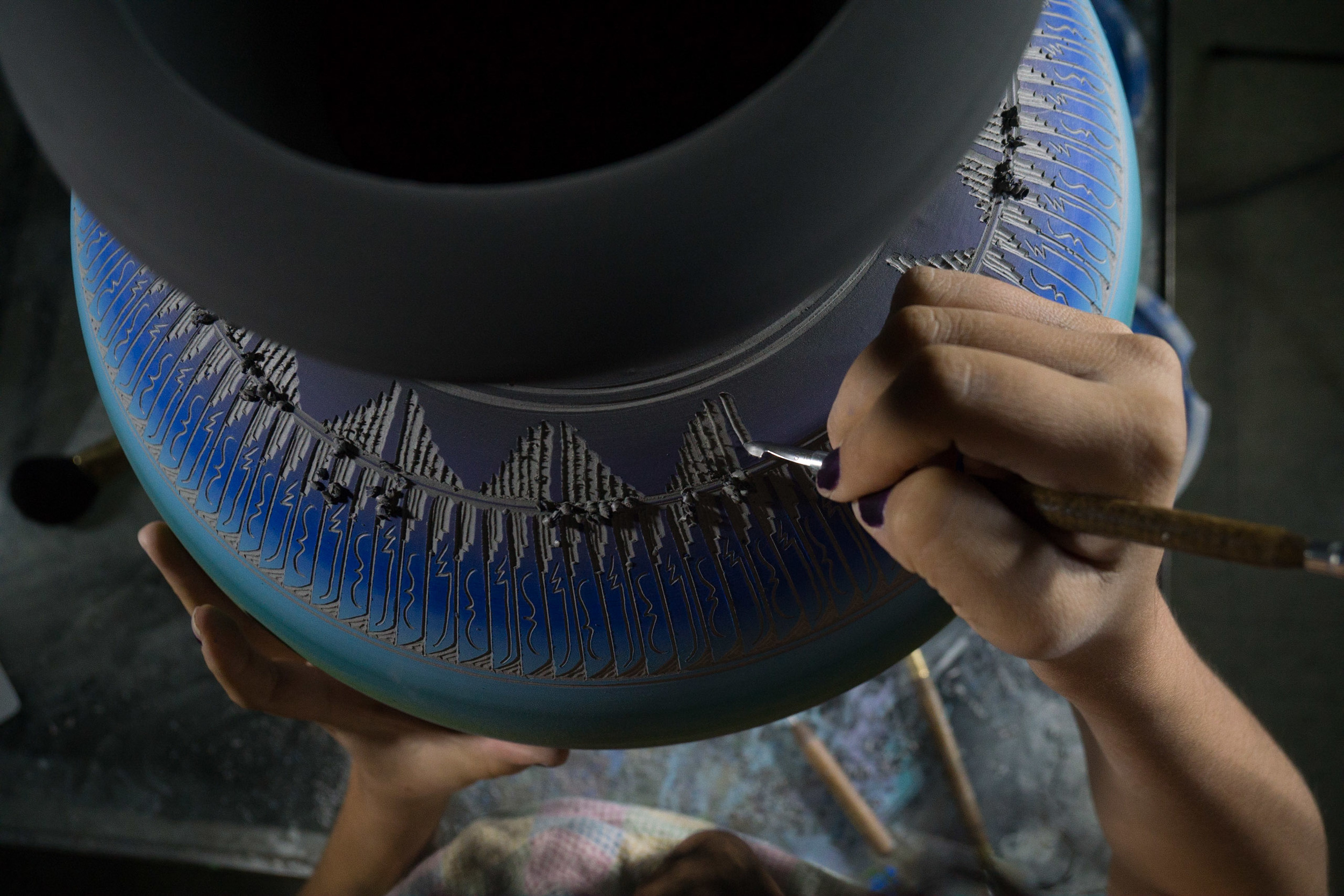

The potter's process

1. Choose a molded pot

The potter begins by choosing the shape of the molded pot that will be used to create a masterpiece. There are hundreds of different possibilities. Some are tall, some are short, some are round, and some are slender, but all take time and care to be made into a unique piece.

2. SMooth the edges using sand paper and sponge

At this point, the pot is grey and rough. The potter sands down the rough edges until the surface is perfectly smooth. Then the potter applies one cool, clean coat of water to soak into the pot at a time.

3. choose paint colors

Once the pot is smoothed from the water and the sponge, the potter chooses bright colors that fit the pot.

4. paint bands of color as the pot spins

Now the potter applies layers of paint in bands around the pot while spinning it on the wheel. Only a very skilled potter can blend colors seamlessly from one to another, like a sunset.

5. carve designs into the surface

The potter then uses different tools to create patterns and symbols, each with unique history and meaning. These symbols can mean something as simple as water or something as complex as a family. Many of the symbols are hundreds of years old, found on ancient pottery around the Southwest.

6. Fire the pot

This is the most nerve-wracking point for the potter. If the wrong amount of water is used, it could ruin the pot. If the paint is too thin, the pot will be streaked. The pot is brought to the correct high temperature and then left to cool slowly on its own. After almost 24 hours, the kiln returns to room temperature and the potter is able to open it and unveil the work of art.

Own a hand-crafted work of art

To order your own one-of-a-kind piece of HIS pottery, call (928) 524-6845 or email development@HISSDA.org.